The Newton–Raphson method is based on a first-order Taylor approximation of a function and exhibits quadratic convergence near a simple root. By employing higher-order approximations, recurrence formulas with higher-order convergence can be constructed.

In contexts where extended- or multiple-precision arithmetic is required,

recurrence formulas with higher-order convergence can significantly reduce computational cost by minimizing the number of iterations needed to reach the desired accuracy. This is particularly important in high-precision environments,

where multiplication tends to dominate the overall computation time. By reducing the number of required multiplications,

high-order recurrence formulas improve the efficiency of numerical methods.

The following examples illustrate such high-order methods applied to the computation of reciprocals and square roots.

The recurrence formula for computing the reciprocal 1/A using Newton-Raphson method is given by

The number of correct significant digits doubles at each iteration.

In contexts where extended- or multiple-precision arithmetic is required, high-order convergence can significantly reduce the computational cost by minimizing the number of iterations needed to reach the desired accuracy.

1/A with cubic (3rd-order) convergence

Introducing hn allows us to express

the iteration error explicitly and to derive higher-order corrections

by series expansion.

Let hn be the error in xn.

With this method the number of correct significant digits roughly triples at each iteration.

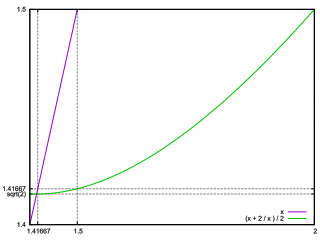

1/A with 4th-order convergence1/A with 5th-order convergence√A of cubic convergenceA similar approach can be applied to the square root calculation.

The standard Newton-Raphson recurrence for computing √A

(the square root of A) is given by:

However, this method has the disadvantage of requiring a division

A / xn at each step,

which can be computationally expensive.

Instead, if we apply the Newton-Raphson method to compute 1/√A,

we can derive a more efficient recurrence formula.

1/√ASince 3/2 and 1/2 are constants,

This formula only involves multiplication—making it computationally more efficient.

Once 1/√A is computed, √A can be obtained simply as:

As in the case of reciprocal approximation, using a higher-order recurrence for 1/√A

leads to faster convergence. Below is a formula derived from the series expansion of 1/√(1 - h).

1/√A of cubic convergenceThe number of significant digits is tripled with each iteration.

hn is equal to the error of xn.

1/√A with 4th-order convergence1/√A with 5th-order convergence1/√A with 6th-order convergenceAs in the case of 1/√A, we use the series expansion of √(1 - h).

√A with 6th-order convergencehn requires / (division),

which may impact performance in extended- or multiple-precision arithmetic.

1/∛A (= A-1/3) with 6th-order convergence1/∜A (= A-1/4) with 6th-order convergence/* _sqrt - compute the square root of x.

* Rev.1.0 (2026-01-29) (c) 2002-2026 Takayuki HOSODA

* SPDX-License-Identifier: BSD-3-Clause

*/

#include <math.h> /* frexp(), ldexp(), NAN */

double _sqrt(double x);

double _sqrt(double x) {

double a, d, h;

int e;

/* Lookup table for scaling factor based on exponent parity */

static const double scf[3] = { M_SQRT2, 1.0, M_SQRT1_2 };

if (x < 0) return NAN; /* Return NaN for negative input */

if (x == 0) return x; /* sqrt(0) = 0 */

/* Range reduction: x = d * 2^e, where d in [0.5, 1) */

d = frexp(x, &e);

/* Initial approximation of 1 / sqrt(d) using 3rd-order polynomial */

/* Approximation error |err| < 5e-4 over d in [0.5, 1] */

a = 2.605008 + d * (-3.6382977 + d * (2.9885788 - 0.9557557 * d));

/* Scaling: convert 1/sqrt(d) to 1/sqrt(x) */

a = ldexp(a * scf[1 + e % 2], -e / 2);

/* Compute residual h = 1 - x * a^2, then apply correction */

/* 6th-order convergence in final refinement */

h = 1 - x * a * a;

a *= (1 + h * (0.5 + h * (0.375 + h * (0.3125 + h * (0.2734375 + h * 0.24609375)))));

return x * a; /* Return sqrt(x) = x * (1 / sqrt(x)) */

}

This code is an implementation for illustrating the algorithm.

For IEEE 754 double precision, the libc sqrt function is faster,

and it is much faster if the processor has a native sqrt implementation.

![[Mail]](/~lyuka/images/mail.gif)