This is a 64-bit integer square root algorithm and its C implementation, designed for 18–24-bit signal processing systems, withminimum rounding error.

Since the square root of a 64-bit integer results in a 32-bit value,

the computation is performed around the lower part of the upper 8 bits of the MSB

in order to avoid overflow and underflow during coefficient multiplications and right shifts.

Values smaller than 0x8000 are scaled up to the upper 16 bits before computation.

The initial value is obtained using a first-order Min?Max?like approximation. Then, the Newton?Raphson method is applied three times to reduce the error to within 1 LSB. Finally, an LSB adjustment is performed to confine the error within±1/2 LSB.

This algorithm is centered around equations (1) and (2).

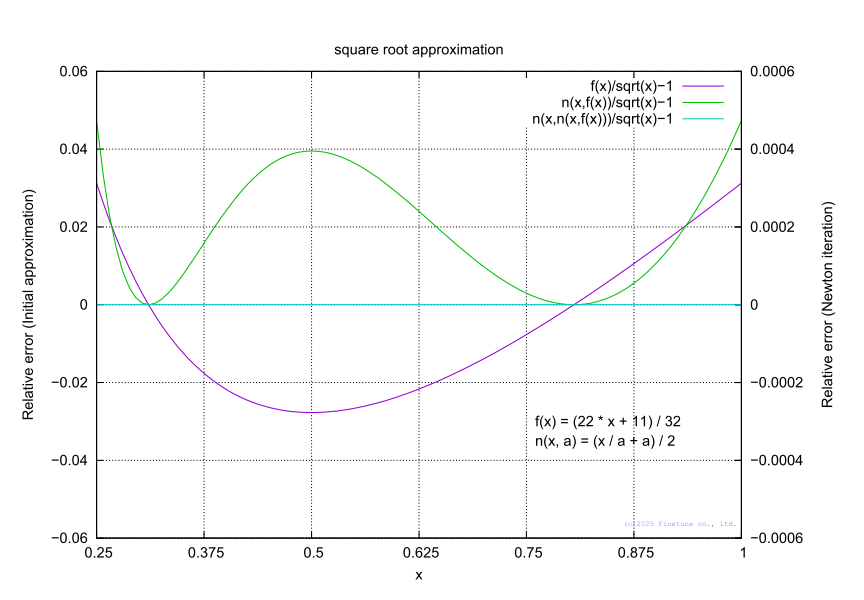

As an initial approximation of the square root over the interval

x ∈ (0.25, 1), the first-order approximation (1) is used, where the denominator is chosen to be a power of two.

With this approximation, an accuracy within ± 0.31 % is achieved.

Error reduction is performed using the Newton–Raphson iteration given by equation (2).

When the function has no multiple roots, the Newton&endash;Raphson method exhibits quadratic convergence in the vicinity of the solution.

The theoretical accuracy after each iteration is as follows:

1st: 4.8×10-4

2nd: 1.2×10-7

3rd: 6.5×10-15

Since

Using the expansion up to the second-order term yields an iteration equivalent to Halley's method, and using up to the third-order term yields Householder's method.

0x3fffffffff) in a 38-bit system is as follows:

error(-1/4..-1/2 LSB) = 68719476736

error(-1/4..+1/4 LSB) = 137438953472

error(+1/4..+1/2 LSB) = 68719476736

sqrt64 returns the integer value that minimizes the error for the square root of a given 64-bit integer.

For negative inputs, the function returns the value as-is without raising an exception.

/* sqrt64 - calculate squre root of given integer value * Rev.1.4 (2025-12-31) (c) 2003-2025 Takayuki HOSODA * SPDX-License-Identifier: BSD-3-Clause */ #include <inttypes.h> int64_t sqrt64(int64_t x); int64_t sqrt64(int64_t x) { int64_t a; // approximation register int64_t t; // scaled '1' int sr; // scaling (for relative domain of (0.25, 1)) int sx; // scaling (for small values) int n_bit = sizeof(x) * 8; // number of digits of given x (e.g. 64 for int64_t) int n_room = 8; // head room if (x <= 0) return x; // netative values are returned unchanged. sx = 0; a = x; if (x < (1LL << (n_bit / 2 - 1))) { // If x is in the lower half of the digits, sx = n_bit / 4; // note that square root halves the digits. a = x = (x << (n_bit / 2)); // enlarge to the upper half of the didits. } a >>= n_room; // scale down to get head-room sr = n_bit / 2 - n_room; t = 1LL << (n_bit - n_room - 2); while (a < t) { // find operating point t >>=2; sr--; } a >>= sr; // now, a / t is in (0.25, 1) t = 1LL << (sr + n_room); // scaled '1' a = (22 * a + 11 * t) / 32; // -3.1e-2 < err < +2.9e-2, a / t in (0.25, 1) a = (x / a + a) >> 1; // 0 <= err < 4.8e-4 a = (x / a + a) >> 1; // 0 <= err < 1.2e-7 a = (x / a + a) >> 1; // 0 <= err < 6.5e-15 if ((x - a) > (a * a)) // the approximation error is always zero or negative a++; // adjust LSB so that the error is within 1/2 LSB if (sx) { a += (1LL << (sx - 1)) - 1; // for round half a >>= sx; } return a; } #ifdef DEBUG #include <stdio.h> #include <math.h> int test_sqrt(int64_t x) { int64_t y; double ref; ref = round(sqrt((double)x)); y = sqrt64(x); fprintf(stdout, "sqrt64(%"PRId64") = %"PRId64" %s %.f\n", x, y, y != ref ? "!=" : "==", ref); return (y != ref ? 1 : 0); } int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { int i; int64_t x, y; if (argc == 2) { sscanf(&argv[1][0], "%" SCNd64 "\n", &x); y = sqrt64(x); fprintf(stdout, "sqrt64(%"PRId64") = %"PRId64"\n", x, y); } else { x = 1LL; for (i = 0; i < 63; i++) { test_sqrt(1LL << i); test_sqrt(x); x = (x << 1) | 1; } } return 0; } #endif

Ĥ The square root of INT64_MAX (0x7fffffffffffffff) is

0xb504f334 (= 3037000500 ) , which exceeds INT32_MAX (0x7fffffff).

Therefore, the return type cannot be int32_t .

A1: Because intermediate values become excessively large in integer arithmetic.

In one example of the Halley update formula:

⛔ Halley's method is fast, but consumes too much dynamic range for integer arithmetic.

A2. The initial error is reduced, but intermediate values become much larger.

For example, using the following second-order Min?Max approximation over

x ∈ (0.25, 1):

the initial approximation error can be reduced to about 0.6 %, which is approximately 0.7 decimal digits better than the first-order approximation.

However, this expression contains an x2 term. In integer arithmetic, this temporarily requires more than double the bit width.

⛔ Increasing the approximation order drastically increases the required dynamic range.

A3. It is possible, but at that point, the approach becomes counterproductive.

Possible workarounds include:✅ Newton?Raphson is not flashy, but it is slim, robust, and predictable.

A4. Safely covering the entire value range in a fully explainable manner.

This implementation adopts:Methods that are gfasth in floating-point arithmetic✅ As a result, the algorithm is also numerically reliable, simple, and highly portable.

may become gdangeroush in integer arithmetic.

In this implementation, dynamic range was the highest priority in all design decisions.

![[Mail]](/~lyuka/images/mail.gif)

© 2000 Takayuki HOSODA.

© 2000 Takayuki HOSODA.